Co-Creating Cranes Landing

Insights

Honoring Culture, Building Equity: Co-Creating 901 Navajo

In the heart of Denver’s La Alma/Lincoln Park neighborhood, a new kind of community is taking shape, rooted in place, people, history, and healing. Mercy Housing’s 901 Navajo development integrates housing with essential services, including a public healthcare clinic, to create a stable and supportive environment where residents can thrive. But, more than a residential building, it’s a space of reconnection and a recognition of the Native American community in Denver — a city that is home to more than 200 tribal affiliations, yet one where Native people have often been invisible in the built environment and beyond.

RATIO has served as architect on this deeply meaningful project, and more significantly, as collaborators and allies. In partnership with Mercy Housing, one of the nation’s largest nonprofit housing developers, and Amaktoolik Studios, a Native American-led design firm;

We’ve embarked on a journey that’s required us to set aside ego, listen deeply, and rethink what it means to truly serve a community.

A Different Approach to Design

Cranes Landing is the first development supported by housing tax credits with a culturally responsive focus on Native American residents in the Denver metro region. So, from the start, Cranes Landing called for a different kind of design process that challenged conventional roles: one where the architect is not the author but the advocate. RATIO’s Gabe Bergeron serves as the project’s principal: “When we were first brought into the project by Mercy Housing, we knew we had the technical expertise, design resources, and urban housing experience to bring the project to life,” as Bergeron expressed. “But we also recognized that our lived experience, as a predominantly non-Native architecture firm, was not sufficient to authentically represent the people this community was meant to serve.

RATIO turned to Amaktoolik Studios, a Native-led firm with deep roots in community-based design and advocacy for Indigenous representation in architecture. Their team, led by Brian Fagerstrom and Lisa Jelliffe, brought more than just design experience. They brought lived wisdom, relationships, and reverence for Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

A Place to Be Seen, Heard, and at Home

Denver’s Native American population is among the most diverse urban Indigenous communities in the U.S., yet have disproportionate rates of housing instability, poverty, and health disparities. For generations, many Native families in the region have felt disconnected from each other and from spaces that reflect their values, identities, and traditions.

Years prior to Cranes Landing taking shape, Amaktoolik’s Fagerstrom and Jelliffe had conducted a needs assessment in partnership with the Native American Housing Circle. Their report illuminated the gravity of the situation. “Our outreach reached a wide cross-section of the Native American community living in the Denver metro area,” explained Amaktoolik’s senior strategist, Lisa Jelliffe. “Nearly a hundred different tribes were represented among the people we spoke with — yet across the entire state, only two tribes have reservations. What we learned went beyond the need for housing and healthcare. People talked about feeling uncomfortable or even unsafe where they lived, and about being cut off from their culture, families, and communities. For Native people, that loss of connection has deep meaning — it affects everything about feeling grounded, secure, and at home within their culture and community.

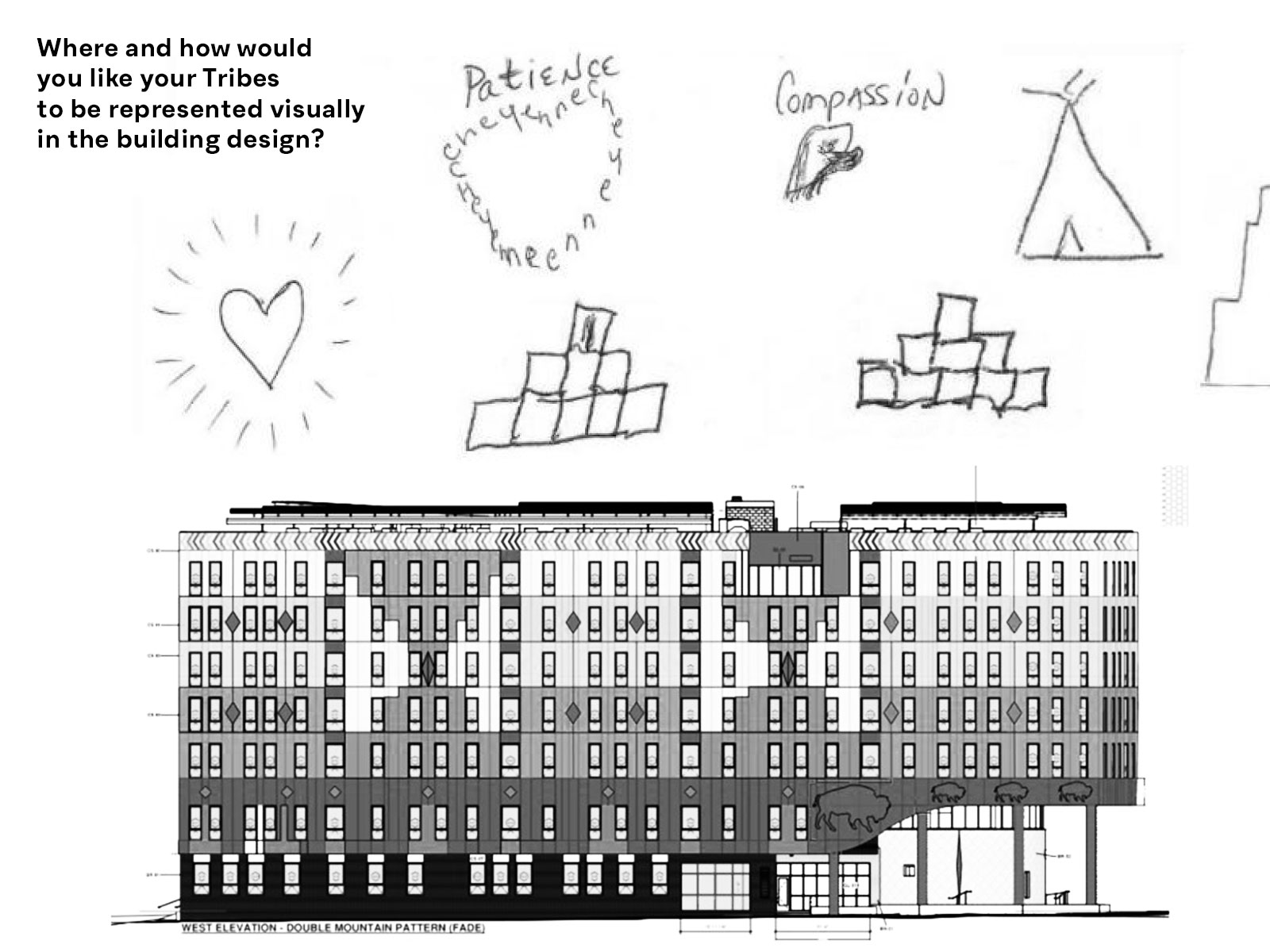

Throughout the design process, community members, tribal elders, Native artists, and advocates have remained engaged in shaping the vision. This isn’t token participation; it is genuine co-creation. Through listening sessions, workshops, and one-on-one conversations, the team has been able to understand the deeper meanings behind spatial needs — how community gathering isn’t a bonus, but a lifeline.

The Role of the Architect as Advocate

This intergenerational housing community with an onsite health clinic will provide 190 apartment homes to families and individuals with low incomes and is designed to create a sense of belonging. Through careful planning and deep community input, the design includes shared gathering spaces and architecture that responds to Indigenous concepts of space, family, and relationship to the land.

RATIO’s role in this project has been to translate vision into form, but always under the guidance of those with the lived experience and cultural knowledge to lead. This approach required humility. It also required reflection on the responsibilities as architects working within communities that have experienced centuries of trauma and harm at the hands of systems including the design profession, which has long played a powerful role in shaping places and culture.

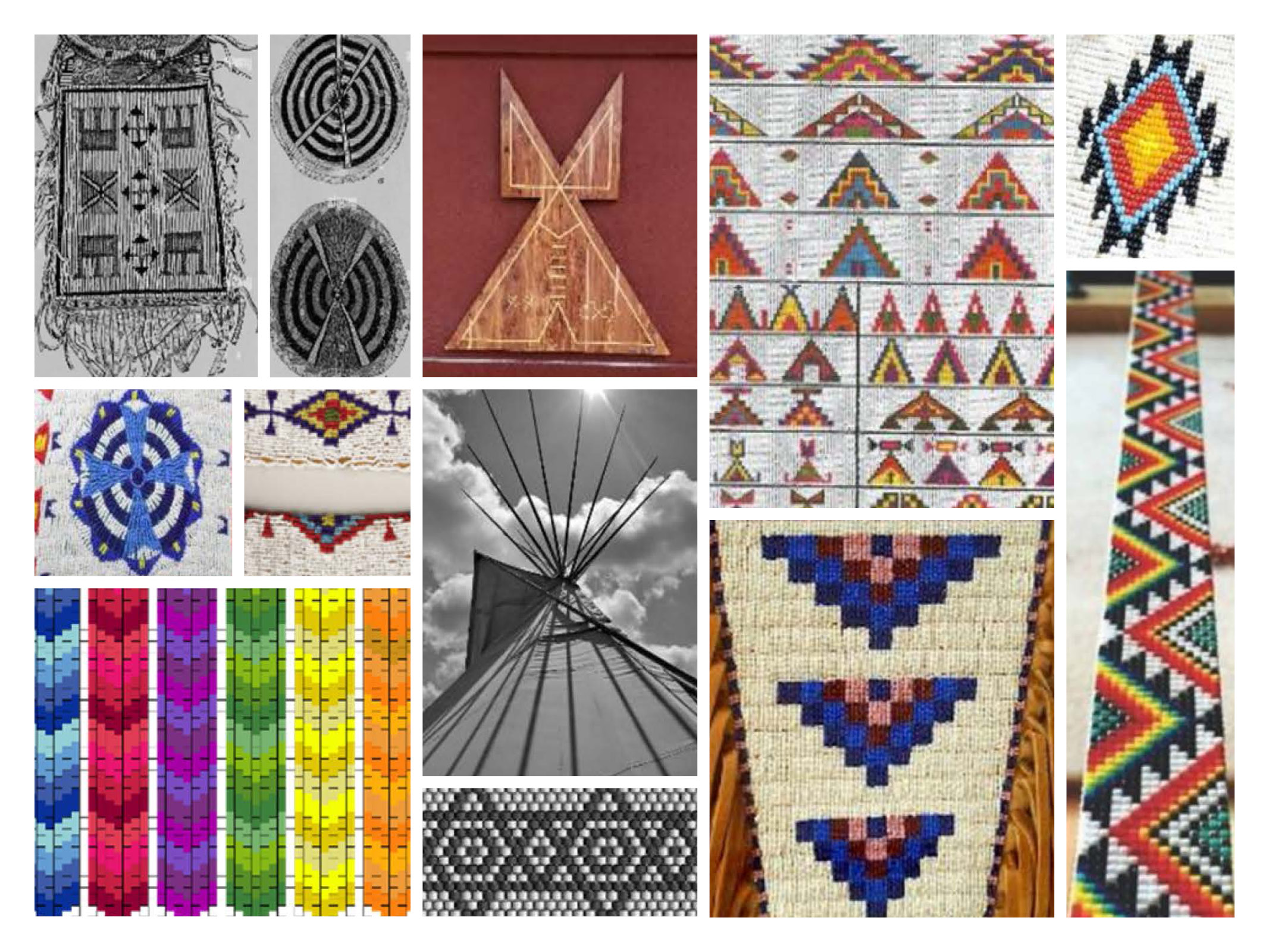

To shape Cranes Landing with authenticity, Amaktoolik Studios’ designers led the charge in crafting the Native design expressions that are so critical to this project’s success in nurturing better connections. For example, the building exterior, on a highly visible urban site, features bold colors and traditional Native patterns that reflect the strength and spirituality of mountains and the transformative energy of lightning. Symbolized by a stepped triangle, these patterns were the direct result of sketches created in focus group conversations with Native community members. RATIO’s designers coordinated the building’s window spacing and other specific dimensions to work with this pattern, under Amaktoolik’s authorship and guidance.

Outdoor spaces are similarly intentional, aligned with the cardinal directions and Native forms of navigation. Inside, a gathering circle offers space for the Native community to come together. At first glance, a round room might feel complicated to design and build, perhaps expensive, especially for an affordable housing community. A pivotal community meeting shifted that perception.

A Model for Future Collaboration

The partnership between RATIO, Mercy Housing, and Amaktoolik Studios has been transformative. For Reid, it’s been successful because of the entire team’s openness. There have not been any preconceived notions about what things should look like, but rather a willingness to listen to all of the ideas and work together to find solutions. And to Bergeron, the partnership has been a reminder that this work can be empowering, and — done right — can start repairing broken connections.

“The design team didn’t decide we’re going to do something for this marginalized community and just do it.” underscored Brian Fagerstrom, Amaktoolik Studio’s founder and CEO. “The team truly engaged and invited participation across that community. Our people have been designing dwellings for centuries — far longer than our architecture profession — so this provides an opportunity to realign design with Native understanding.”

Cranes Landing is not a monument, it’s a home. And providing stable, affordable housing for underserved communities is its top priority. But it also serves as a physical space where multi-generational families can thrive, where elders are honored, and where children can grow up seeing their identities reflected in the world around them.

This project is also a model. It demonstrates that with intention, collaboration, and a willingness to cede authorship, design can be a tool of equity. It shows that community-led design means elevating meaning, not compromising quality. And it proves that listening is one of the most powerful design tools we have.